[This post includes a short video best experienced from the Just a Thought website. Please click the link above.]

“Our country’s honor calls upon us for a vigorous … exertion; and if we now shamefully fail, we shall become infamous to the whole world.” ~ George Washington

The same can be said of America in the current moment.

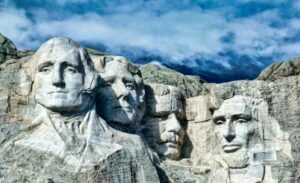

If Washington were to return to our country today he would see a land in which honor is held in disrepute.

- dishonorable people are highly esteemed

- dishonorable people are elected to high office

- dishonorable conduct is routinely applauded, and

- dishonorable beliefs are roundly celebrated

How we got here — one could debate. That we’ve arrived — is indisputable.

There was a time when people esteemed honor.

My friend Joe Nagy looks at how honor is lost:

Lost Honor

In November 2007 my wife and I visited our son Nate in New York City at the start of his second year of college. We went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for the afternoon, and Nate took a liking to Rembrandt’s painting titled “Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer.” Afterwards he bought a poster of the painting in the gift shop. Here’s what I wrote to him afterwards:

Dear Nate,

Here’s why I like Rembrandt’s painting of Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer.

The museum’s note describing the painting suggested that Rembrandt was creating an allegory, Aristotle standing for Reason, Homer for Honor.

Reason is pondering Honor, with a look of concern, perhaps of longing, perhaps tinged with regret.

Why honor?

Tradition tells us that Homer was a blind poet composing some 250-300 years before Aristotle’s time. We know very little about him. We don’t know where he lived or what he looked like. Yet the Greeks of 5th Century B.C. considered the Iliad and Odyssey to be the highest expression of Greek culture – they defined what it meant to be a person of honor and courage.

Why reason?

Aristotle lived in Athens after the fall – Athenians through pride and arrogance entered into a devastating war with Sparta and lost. However, Athens was still the school of Hellas, and Aristotle above all others was the schoolmaster. He defined the academic disciplines that we still follow today, and he categorized and described everything that was knowable.

The historian David McCullough reminds us that the people we study in history did not live in the past.

They lived in the present, their present.

Aristotle’s time was present time, and it was full of conflict, uncertainty, and danger. Aristotle probably looked at the Athens of his day and thought that they had lost something valuable when they achieved power and glory.

He might have looked back 300 years to Homer as we look back to George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and John Adams.

He might have wondered what all this wealth and knowledge had brought, if in the process Athenians had lost their core values.

The genius of Rembrandt’s painting, to me, is that he performs a trick that only art can do.

Rembrandt catapults Aristotle into the present – Rembrandt’s present.

He depicts him as a wealthy, influential Dutchman of his day – someone very much like the people whose portraits Rembrandt regularly painted. Holland in the 17th century was a trading giant and prosperous beyond all other nations of the time.

Perhaps Rembrandt was contemplating what the Dutch had lost when they achieved great wealth. He must have seen at close range the lives of the rich and famous who were so eager to hire him.

He recorded the faces of the Jeff Bezos’s and Donald Trumps of his time, and perhaps he didn’t like what he saw.

And so he draped his Aristotle in the robes and gold chains of a newly rich Dutchman, and had him ponder the bust of a blind, poor, unknown poet whose face we will never know, but whose works will last for all time.

Perhaps Rembrandt was reminding those whose portraits he painted: I can record your image for future generations, but they will judge you by your actions.

Choose wisely.

Sincerely,

Dad

Abraham Lincoln made a similar observation at the outset of the American Civil War:

Fellow-citizens, we cannot escape history. We of this Congress and this administration, will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance, or insignificance, can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation.

We say we are for the Union. The world will not forget that we say this. We know how to save the Union. The world knows we do know how to save it. We — even we here — hold the power, and bear the responsibility. In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free — honorable alike in what we give, and what we preserve. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth.

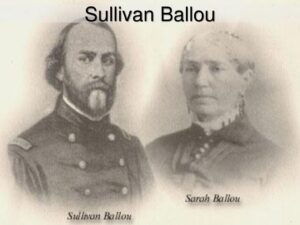

One man who took up this call to honorable action was Major Sullivan Ballou, of the 2nd Rhode Island Volunteers

On the eve of the battle of Bull Run Major Ballou wrote this letter to his wife Sarah:

That we might recover the meaning of honor in our time

Just a thought…

Joe and Pat