Neil Vance remembers Floyd Stanley…

His voice was unmistakable. Although we hadn’t talked in several years, I was sure it was him immediately. After establishing that it was really me, he said, “I need a favor.” Oh no, I thought. They’re foreclosing on the shopping center and he wants my help in arranging another loan.

I made my decision before his sentence was even finished. I can’t afford the time off, I can’t afford the trip to Chicago, and I can’t afford the agony of working on that damn shopping center again.

I steadied myself to give my friend of 15 years a resolute NO. “Floyd,” I started,” I just can’t…” He interrupted, “No, it’s nothing like that. I need you to sign a deed. We’re refinancing the center with a much better mortgage and you and me are the two names on the original deed. Things go well. I don’t need you to do anything except sign the deed.”

I suppose my sigh of relief was audible, for he then laughed. “Things really are fine,” he continued, ”but the food store lady is selling her share and we can get much better loan terms.”

It’s truly a miracle, I thought. For once the shopping center is good news. And my mind wandered over a montage of events and people — good and bad — that made up that miracle.

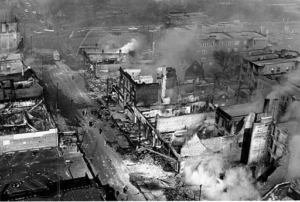

For some, the riots of the late 1960’s are written as history. They, however, remain perpetually fresh for those who actually experienced them.

The riots — particularly April 5, 1968 following Martin Luther King’s murder — left the west side of Chicago a barren wasteland. As the community residents looked at their situation — in community meetings and informal conversations — there was one constant in their hopes and aspirations: they wanted a local, community-owned shopping center.

We, living in the ghetto as a symbol of dedication, were asked to help. Although our intentions were impeccable, our skills in economic development were lacking. Nevertheless, we said we would help. We all felt that it would be far better to support a local Black businessman to run the project than import someone who wasn’t from the neighborhood. In retrospect, we probably couldn’t have gotten anyone to come to the west side, anyway.

So we turned to Floyd, the local barber; Tommie Lee, the local liquor store man and Willie, the local hardware store owner. We told them if they would work side by side with us, we would do everything possible to arrange financing and training to set them up in a neighborhood shopping center.

Willie didn’t last long before he dropped out and Tommie Lee not much longer, but Floyd stuck it out from the very beginning, through all the disappointments and false starts. Floyd was always available to go on appointments — whatever it takes, was his attitude.

It didn’t take us long to discover there was no federal loan program for inner city shopping centers (as there was for housing.) We quickly learned that we needed to raise considerable amounts of money to have enough equity to get a bank loan that would be bearable for the shopping center tenants.

So we set out to raise the money.

There were the original donors and people would step in to help when there was trouble. Over the years, many good people contributed time and money. It always seemed like there were problems, but there were always caring people ready to help.

What made the center a success in the long run was its community base. One story best illustrates this:

Conventional shopping center wisdom has it that our center should have been a “strip center” — one long row of stores. Floyd and the others insisted that it be a “mini-mall,” arguing that the glass windows of a strip center would have to be covered by unsightly security bars.

They were right, of course.

So the center was built — the first locally-owned, new construction on the west side of Chicago since the 1968 riots. It was and still is a very attractive building.

And there were problems. At the time, they seemed unending. The curious thing is that I can hardly remember any specific problems now, because Floyd said something when he called that erased my memory of the shopping center as a problem. When I asked about his family, he proudly rattled off which universities his three kids attended:

- Michigan State

- University of Illinois

- University of Arkansas

I then understood the real reason for his call, besides signing the deed. He wanted me to know that he, son of a Mississippi sharecropper, had put three kids through college with a fourth soon to start.

At a time when there are more Black men in jail than university, Floyd had put three kids through college! It makes the shopping center — time, money and problems — worth every moment.

Just a thought…

Neil Vance

(Postscript from Pat: A couple years ago I met up with Floyd Stanley at the funeral of Verdell Trice, another sacred friend from the west side. He was well into his eighties, blind and walked with a cane, but there at his side were his three boys, standing tall and erect. After the service I went over to him, took his hand and whispered in his ear best wishes from Neil and myself. A big, broad smile came over his face — a sacred friend forever.)

Copyright © 2019 Just A Thought. All Rights Reserved.

Would you like to submit a post to Just A Thought? To learn more, please click here.