Facing the consequences of our actions is the last thing any of us want.

In fact, whenever we sow the wind, we pray that we won’t have to reap the whirlwind. We start bargaining with God/Fate/The Way Life Is:

“Okay, I’ve learned my lesson. I’ve changed. I won’t make this mistake again. Just give me one more chance. Please please please please don’t crush me down in the dust again.”

And once again, we end up lying face down with our mouth in the dirt.

I’ll always remember, Pat, your story about asking your mentor: How do you know when you’ve hit bottom?

His answer: When you stop digging.

And yet, it is the experience of being ground into the dust that makes it possible for us to be reborn in the spirit.

The ancient Greeks knew this. Aeschylus wrote

It is God’s law “that he who learns must suffer.”

How bad?

This bad:

“And even in our sleep pain that cannot forget, falls drop by drop upon the heart, and in our own despite, against our will, comes wisdom from the awful grace of God.”

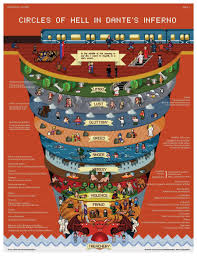

In all great journey myths, from Beowulf to the Odyssey to Dante’s Inferno, the hero must make a journey to the underworld. It is not a journey he seeks, but it is forced upon him.

Once there, he faces a near-death experience. If he survives, he is transformed. He sees his identity in a new light. Only then is he capable of fulfilling his destiny.

George Lucas studied these archetypal journey tales when he was writing the script for Star Wars. In “The Empire Strikes Back,” Luke Skywalker is not yet ready for a showdown with Darth Vader.

He would be eaten alive.

So he makes a journey to a distant planet to train with a famed Jedi knight. Instead of finding some great warrior, he finds the puny Yoda.

Skywalker is put through a series of grueling exercises.

In the last test, he must enter a cave for a life-and-death encounter. In a dreamlike sequence, he comes face to face with Vader. They duel, and Skywalker slays Vader.

When he pulls off Vader’s mask, he sees – himself.

We are our own worst enemy. And we will not conquer ourselves unless we make that terrifying journey within – as Dante did in The Inferno – and come face to face with our own weaknesses, uncontrollable desires, and deep-seated fears. And miracle of miracles, when we do face those dreaded monsters, they vanish.

They were never real. They never had the power to touch us.

When Dante reaches the ninth circle of hell he encounters a giant two-headed Satan waist-deep in a frozen lake. Dante must climb over Satan’s back to exit hell.

When he first entered hell, he fainted at the sights and sounds there.

- Now he is without fear.

- Evil has no power over him.

- He has gone down into the dark, so that he can go up into the light.

My first job after college was as a journalist at a weekly newspaper in the paper mill town of Berlin, New Hampshire. The town smelled like hell – literally. The mill emitted sulphur fumes that settled on your car overnight and ate off the paint.

I was living alone, working six days a week, and after a year of this I felt as if I had reached a breaking point. I was so lonely that I would envy strangers walking down the street, thinking that at least they had a life. They had friends. They were free to do things. I felt trapped in an endless cycle of drudgery.

My only solace was the daily lesson on the editorial page of the Christian Science Monitor. My boss was a Christian Scientist who had worked for the Monitor and won a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting. He was busy writing a book, and left me to run the paper.

So I read the Monitor each day at lunch over my desk.

One day the Monitor’s lesson was an excerpt from “Letters to a Young Poet,” written by the Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke.

Rilke had written the letters at the turn of the century to a 19-year-old military cadet who was disillusioned with the army and was writing poetry. He asked Rilke for advice. Rilke responded with ten letters of extraordinary insight and wisdom, given that Rilke himself was only 27.

I don’t remember now which of the ten letters that the Monitor published. But it turned on a light in the dark. I have never forgotten the experience. Later I bought the book.

Here is one of my favorite passages, from Letter 8:

“We have no reason to harbor any mistrust against our world, for it is not against us. If it has terrors, they are our terrors; if it has abysses, these abysses belong to us; if there are dangers, we must try to love them. And if only we arrange our life in accordance with the principle which tells us that we must always trust in the difficult, then what now appears to us as the most alien will become our most intimate and trusted experience. How could we forget those ancient myths that stand at the beginning of all races, the myths about dragons that at the last moment are transformed into princesses? Perhaps all the dragons in our lives are princesses who are only waiting to see us act, just once, with beauty and courage. Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that wants our love.”

It took me a long time to understand that the dragons were not without, but within. And they were our friends.

Just a thought…

Joe